Clinical examination of the nose and nasopharynx

Applied basic science

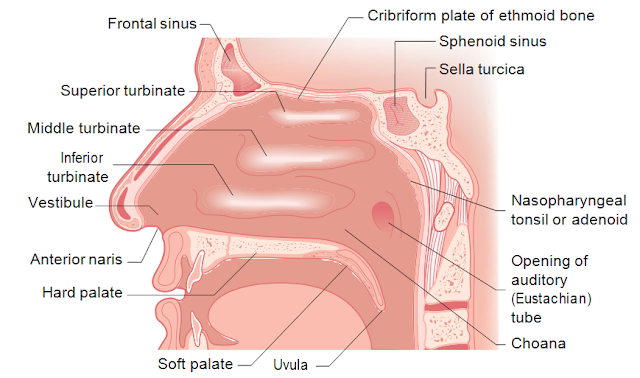

The nose is made up of a framework of bone and cartilage, lined with skin on the outside and with mucosa on the inside (Fig. 16.1). The nasal mucosa is lined for the most part with ciliated columnar epithelium except for a small area of highly spe- cialized olfactory mucosa, which is receptive to scents and odours and communi- cates with the olfactory nerve. The largest of the cartilages that makes up the nose is the septal cartilage, dividing the nasal cavity in two. The anterior part of the nose is termed the nasal vestibule. The posterior nasal apertures are the choanae. These open to the upper part of the pharynx – the nasopharynx.

The lateral wall of the nose is contoured with three bony swellings, covered with mucosa, projecting into the nasal cavity. These are the turbinates, which can become engorged and swollen when inflamed- ‘rhinitis’.

Functions of the nose

• A conduit for the passage of air-the first part of the respiratory tract.

• Part of the respiratory defence against infection.

• Warms and humidifies inspired air.

• Olfaction.

The sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are a series of air-filled cavities that communicate directly with the nose. They are lined with nasal mucosa and are subject to the same diseases as the nose itself – notably inflammatory processes. Hence the term ‘rhinosinusitis’ is more accurate than ‘sinusitis’.

The maxillary sinus or ‘antrum’ is the largest of the sinuses with a capacity in the adult of approximately 15 mL. The orbit lies above and the hard palate with the roots of the second premolar and the first two molar teeth forms the floor. Medially the antrum is separated from the nose by the lateral nasal wall made up of the middle and inferior turbinate bones, each with a corresponding recess or ‘meatus’ below it (Fig. 16.1).The ethmoidal sinuses form a honeycomb of air cells between the ‘lamina papy- racea’ or thin bone at the medial wall of the orbit and the upper part of the nose. An upward extension forms the fronto-nasal duct draining the frontal sinus. The frontal sinus is within the frontal bone in the forehead and the sphenoidal sinus is in the midline within the sphenoid bone behind the nose.The openings of the sinuses under the middle turbinate form the ostiomeatal complex. It is now recognized that abnormality of this area leads to failure of sinus drainage and thence to sinusitis. Abnormalities may be structural, as with a large aerated cell blocking the ostial openings. Functional anomalies such as oedema, al- lergy or polyp formation can also obstruct the ostiomeatal complex.

The maxillary sinus or ‘antrum’ is the largest of the sinuses with a capacity in the adult of approximately 15 mL. The orbit lies above and the hard palate with the roots of the second premolar and the first two molar teeth forms the floor. Medially the antrum is separated from the nose by the lateral nasal wall made up of the middle and inferior turbinate bones, each with a corresponding recess or ‘meatus’ below it (Fig. 16.1).The ethmoidal sinuses form a honeycomb of air cells between the ‘lamina papy- racea’ or thin bone at the medial wall of the orbit and the upper part of the nose. An upward extension forms the fronto-nasal duct draining the frontal sinus. The frontal sinus is within the frontal bone in the forehead and the sphenoidal sinus is in the midline within the sphenoid bone behind the nose.The openings of the sinuses under the middle turbinate form the ostiomeatal complex. It is now recognized that abnormality of this area leads to failure of sinus drainage and thence to sinusitis. Abnormalities may be structural, as with a large aerated cell blocking the ostial openings. Functional anomalies such as oedema, al- lergy or polyp formation can also obstruct the ostiomeatal complex.Examination of the nose

Illumination and inspection

The first requirement is adequate lighting. Use a headlight, an endoscope or a head- mirror to reflect light from an adjustable strong light source. All of these take some training and experience to use well. A bright torch or better still an auriscope with the largest speculum that will fit into the nasal cavity provides a good alternative (Fig. 16.2).

First inspect the exterior of the nose. Look for asymmetry of the nasal bones and gently lift the nasal tip to look for any deviation of the septum and any evidence of inflammation of the skin around the entrance to the nasal cavity (vestibule).

The nasal airwayNow assess the nasal airway. You can do this by gently occluding one nostril at a time and asking the patient to breathe in through the other side, or by holding a cool polished surface such as a metal tongue depressor below the nostrils. The areas of condensation from each side of the nose can be compared.

Anterior rhinoscopy and nasendoscopyMost students are unaware of the interior dimensions and relations of the nose, which extends horizontally backwards for 65–76 mm to the posterior nasal apertures or ‘choanae’. Remember that the interior of the nose is much more horizontal than most students think and that the nasal mucosa is very sensitive! When you look in remember to look ‘back’ rather than ‘up’ (Fig. 16.2). The inside of the nose may be obscured by mucosal oedema or septal deviations. A good way to test the patency of the nasal airway especially in children, is to use a cold metal spatula under the nostrils to see the condensation pattern of expired air (Fig. 16.3).ENT surgeons will sometimes use a Thudicum’s speculum (Fig. 16.4), which is in- troduced gently into the nose. In children, a speculum is often not necessary as an adequate view can be obtained by lifting the nasal tip with the thumb.Nasal endoscopes have improved greatly in recent years and rigid endoscopy is now the standard way to inspect the interior of the nose. The instrument is intro- duced through the nose and the nose and nasopharynx (postnasal space) can be easily seen, allowing photography and simultaneous viewing by an observer.

On looking into the nose the anterior septum and inferior turbinates are easily seen (Fig. 16.5). It is a common error to mistake the turbinates for a nasal polyp. Turbinates are sensitive, and are attached to the lateral nasal wall. A polyp is often greyish, translucent and insensitive to touch.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق

من فضلك اكتب تعليقا مناسبا