Acute coryza

The common cold is the result of viral infection but secondary bacterial infection may supervene. It is self-limiting and no treatment is required other than an antipy- retic, such as paracetamol. Discourage the prolonged use (more than 5 days) of va- soconstrictor nose drops owing to their harmful effect on the nasal mucosa (rhinitis medicamentosa). Many patients use menthol inhalations, systemic decongestants and a variety of cough linctus preparations, and find these helpful in controlling symptoms, but evidence of any sustained benefit is weak.

Nasal vestibulitis

Both children and adults may be carriers of pyogenic staphylococci, which can pro- duce infection of the skin of the nasal vestibule. The site becomes sore, fissured and crusted. Treatment consists of topical antibiotic/antiseptic ointment. Consider sys- temic flucloxacillin in more severe cases. In children with persistent vestibulitis look for a nasal foreign body.

Furunculosis

An abscess in a nasal hair follicle

is rare but must be treated seriously as it can spread rapidly and lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis and meningitis. The

tip of the nose becomes

red, tense and painful.

Give systemic antibiotics

without delay. Drainage may be

necessary but should be deferred until the patient

has had adequate antibi- otic treatment

for 24 h. In recurrent cases, exclude

immunodeficiency.

Acute sinus infection

Aetiology

Most cases of acute sinusitis are secondary

to acute viral illness, e.g. coryza, which causes nasal mucosal oedema and interferes with ventilation and mucous clearance from the

sinuses. The paranasal sinuses become infected as part of generalized in- fection

of the nose and sinus mucosa – rhinosinusitis. Usually more

than one sinus is involved (pan-sinusitis; Fig. 18.1). Bacterial infection supervenes causing puru- lent rhinorrhoea. The causative organisms are usually pyogenic, e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae or

Staphylococcus pyogenes. Anaerobes may be involved

especially in dental infections.

Many patients have a background of rhinitis, often allergic in origin, which predisposes them to episodes of ostiomeatal complex obstruction and sinus infection.

In about 10% of cases of maxillary sinusitis

the infection is dental in origin and has

spread from the upper molars

or premolars. Occasionally, infection follows the

entry of infected material, e.g. after diving

– water is forced through

the ostium into the sinus.

Clinical features

•

Nasal obstruction.

• Nasal discharge (rhinorhoea).

• A feeling

of ‘congestion’ in the nose and face.

• Facial pain. In maxillary sinusitis the pain is mainly over the cheeks;

ethmoidal and frontal sinusitis cause periorbital pain and headache, and sphenoidal sinusi- tis

causes severe deep-seated headache.

•

Pyrexial illness.

• Mucopus in the nose.

• Tenderness over the involved sinuses.

• Cheek swelling may indicate a dental abscess.

The diagnosis should be made clinically. Acute sinusitis typically resolves but may recur.

X-rays are not

needed but CT scanning can be very helpful if there are complica- tions.

Treatment

•

Adequate analgesia

•

Antibiotics. If the nasal discharge is mucopurulent, Cefaclor is a useful first-line.

•

Surgery: If the ostiomeatal complex is completely obstructed there may be severe pain due to retained pus

(empyaema). Initial treatment is medical but surgery may be necessary. Drainage of the sinuses is nowadays by endoscopic surgery of the ostiomeatal area under the middle turbinate – functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS).

Developments in endoscopic instruments now allow inspection

of the sinus ostia and interior of the

paranasal sinuses.

Ostial enlargement and

removal of polyps and cysts

can be

performed. The ostiomeatal

complex under the middle turbinate

is opened up.

This allows a more ‘physiological’ drainage of the antrum than was possible before the development of

endoscopic endonasal surgery and ‘antral washout’ – insertion

of a trochar

into the antrum

via the nasal cavity with

aspiration of the contents

of the antrum –

is now rarely performed. Apiration of an empyaema by whatever means brings dramatic relief.

Refer immediately if

you

suspect complications- e.g. severe headache, neurological changes

or eye changes

Complications of acute rhinosinusitis

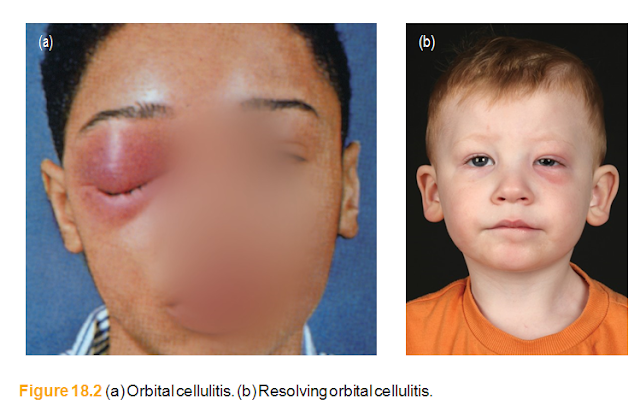

Complications may arise if the infection spreads beyond the bony walls of the si- nuses (Fig. 18.2). These are rare in Western communities but still a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Beware of the patient with sinusitis who de- velops severe headache, swinging pyrexia or neurological signs:• Orbital complications (cellulitis or abscess) are characterized by marked oedema of the eyelids, diplopia, redness and swelling of the conjunctiva (chemosis). Prop- tosis indicates severe orbital involvement. Commence intravenous antibiotics im- mediately and ask for an urgent ENT opinion. Resolution usually follows intensive antibiotic therapy but surgical drainage is required urgently if there is any change in vision. Loss of colour discrimination is an early sign of impending visual loss.

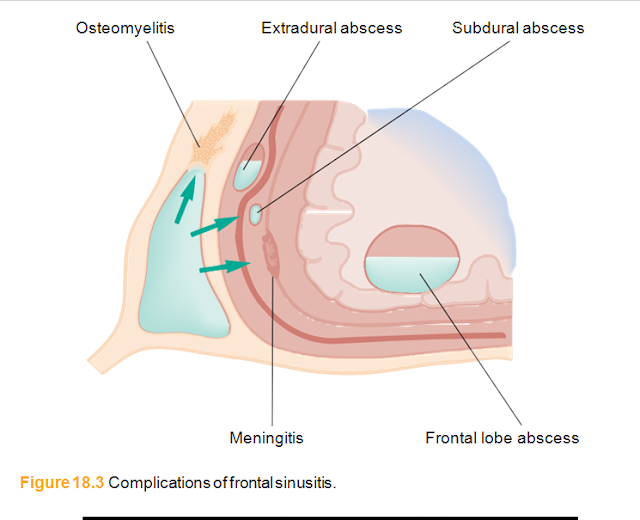

• Meningitis, extradural and subdural abscesses may occur and should be treated as neurosurgical emergencies.

• Cerebral abscess (frontal lobe). Any patient with a history of recent frontal sinus infection headaches or who exhibits any abnormality of behaviour should be sus- pected of a frontal lobe abscess.

• Osteomyelitis of the frontal bone is characterized by persistent headache and oedema of the scalp in the vicinity of the frontal sinus. X-ray signs are late, and by the time they become apparent osteomyelitis is well established. Intensive antibi- otic therapy combined with removal of diseased bone is necessary.

• Cavernous sinus thrombosis is very rare. Proptosis, chemosis (corneal oedema) and ophthalmoplegia characterize this dangerous complication (Fig. 18.3).

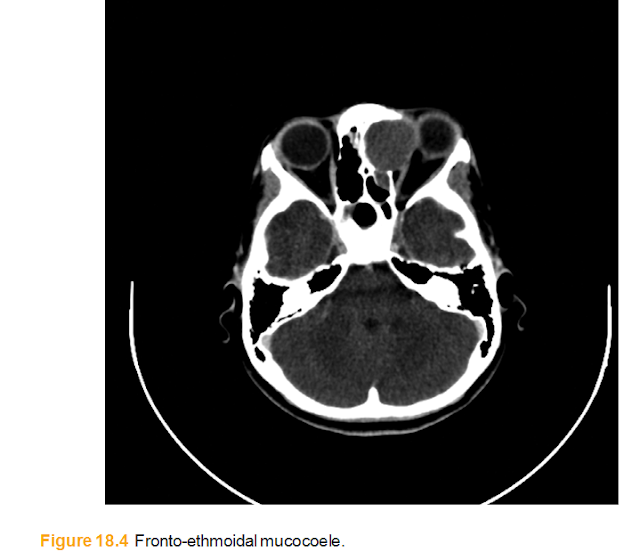

• Poor sinus drainage can cause a bony swelling as secretions build up in the obstructed sinus- ‘mucocoele’. (Fig. 18.4) Treatment is surgical.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق

من فضلك اكتب تعليقا مناسبا